The Enduring Legacy of Graham Greene: A Champion of Authentic Indigenous Storytelling

The world of cinema and stage mourned the passing of Graham Greene, the celebrated Canadian First Nations actor, who died at the age of 73. Known for his profound ability to imbue characters with quiet strength, understated humor, and undeniable authenticity, Greene’s four-decade-long career was instrumental in reshaping and elevating Indigenous representation across film and television. His work transcended mere performance, becoming a powerful statement on dignity, resilience, and the multifaceted nature of Indigenous identity.

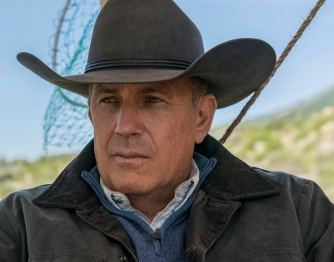

Greene’s international breakthrough came with his indelible portrayal of Kicking Bird in Kevin Costner’s epic western, Dances With Wolves (1990). While the film garnered praise for its revisionist approach to the western genre, its most genuinely progressive and impactful decision was the casting of Native American and First Nations actors in pivotal roles, with significant portions of dialogue delivered in Lakota. Greene’s performance as the spiritual heart of the Sioux community stood out, embodying a wise and compassionate holy man who gradually extended trust and kinship to a white Union lieutenant. He imbued Kicking Bird with a depth and nuanced humanity that steered clear of sentimentality, earning him an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor—one of the film’s impressive twelve nominations.

Remarkably, Greene’s iconic casting in Dances With Wolves almost didn’t happen. He later recounted that director Kevin Costner initially overlooked him until casting director Elisabeth Leustig, along with her team, championed his cause. Greene recalled their insistence, “Elisabeth and the girls ganged up on Kevin. They said, ‘This guy’s right for the part.’” The role demanded more than just acting prowess; it required a linguistic commitment. Greene, not a Lakota speaker, faced the formidable challenge of learning his dialogue phonetically. “I had no idea what I was saying and I had to learn it phonetically,” he told True West magazine in 2021. His dedication was total: “I’d be running 10 miles a day with my headphones on, mumbling away in Lakota. People thought I was crazy.” This anecdote speaks volumes about his commitment to authenticity and the lengths he went to honor the characters and cultures he portrayed.

Born an Oneida in Ohsweken, Ontario, and raised on the Six Nations Reserve, Greene’s journey to acting was not conventional. He embarked on his career in the 1970s after a series of blue-collar jobs, a testament to his grounded nature. A chance encounter with the theatre led him to study at the Centre for Indigenous Theatre in Toronto in 1974. He honed his craft on stage before transitioning to the burgeoning worlds of film and television, laying the groundwork for a career that would profoundly influence the landscape of Indigenous representation. When his Oscar nomination for Dances With Wolves coincided with his starring role in an Ottawa stage production of Tomson Highway’s Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, and the theatre marquee was updated to reflect his newfound acclaim, Greene, ever humble, demanded its removal. “Take it down,” he insisted. “It’s not about me.” This moment encapsulated the humility and resolve that would characterize his entire professional life.

This blend of modesty and unwavering principle defined Greene’s approach to his art. Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium, he meticulously built a substantial body of work, refusing to be pigeonholed. His filmography became a diverse tapestry, including roles in Thunderheart (1992), where he again explored Native American themes, and mainstream hits such as Maverick (1994), Die Hard With a Vengeance (1995), and The Green Mile (1999). He also appeared in critically acclaimed independent films like Transamerica (2005), portraying a tribal elder in The Twilight Saga: New Moon (2009), a judge in Molly’s Game (2017), and a tribal police chief in the neo-western crime thriller Wind River (2017). Each role, regardless of its prominence, benefited from Greene’s unique gravitas and ability to infuse even the smallest parts with dignity.

Beyond his performances, Greene was an outspoken critic of the entertainment industry’s often myopic and stereotypical portrayal of Indigenous characters. He famously articulated his frustration in 1992, stating, “I’m tired of being mystical and stoic.” He recounted early career experiences where he reluctantly accepted roles requiring him to adopt stereotypical mannerisms, forced to “grunt a lot” and avoid smiling to “get your foot in the door.” This struggle for authentic representation was a constant undercurrent throughout his career. Even after his Oscar nomination, he faced blatant bias. He once walked out of an audition for Tony Scott’s Crimson Tide (1995) after the director asserted, “I can’t see a Native American on a sub.” Greene coolly countered that four of his uncles had served on submarines, then departed, later reflecting, “To hell with you. I’m not gonna chase you around for a role.” This resolute stance, prioritizing his integrity over career advancement, underscored his commitment to challenging entrenched prejudices.

Despite his willingness to critique industry shortcomings, Greene preferred to keep politics separate from his personal life, telling the Orlando Sentinel, “I’m not a big political animal. I’ve got too much trouble worrying about my mortgage and how to run my fax machine.” This pragmatism did not diminish his impact; rather, it emphasized that his advocacy for accurate representation stemmed from a deep personal conviction rather than a political agenda. In his later years, Greene relished the opportunity to explore more complex, even villainous characters. He found great satisfaction in portraying Malachi Strand in the TV series Longmire (2014–17) and a shape-shifting casino boss in Goliath (2019). “Being nice all the time—it’s boring,” he once quipped, illustrating his desire to delve into the full spectrum of human experience on screen.

His later work continued to resonate with audiences and critics alike. He appeared in Taika Waititi’s acclaimed series Reservation Dogs and HBO’s highly successful The Last of Us (both 2023), further cementing his status as a versatile and sought-after performer. In the horror-comedy Seeds (2024), he played a fictionalized version of himself as a true-crime host turned spirit guide. Director Kaniehtiio Horn fondly remembered her first encounter with Greene’s acting in the 1991 film Clearcut, noting, “He was one of the first roles where we could actually cheer for the Indigenous character. It was cathartic—for a lot of Indigenous people.” This sentiment perfectly encapsulates Greene’s groundbreaking impact: he provided audiences, particularly Indigenous ones, with characters they could see themselves in, characters who embodied strength, complexity, and agency, shattering centuries of one-dimensional portrayals.

In June 2025, Greene’s extraordinary contributions were recognized with the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for lifetime artistic achievement in Canada, a fitting tribute to a career defined by excellence and pioneering spirit. Reflecting on his extensive career, Greene offered invaluable advice to young actors: “Start with theatre. You’ve got to learn discipline or you won’t last long. They ask, ‘How did you last this long, Mr. Greene—40-some years?’ And I say, ‘I’ve got a thick skin and a hard head.’” This practical wisdom, born from decades of navigating a challenging industry, serves as a powerful reminder of the grit and determination required to build a lasting legacy.

Graham Greene is survived by his wife, actress Hilary Blackmore, and a daughter, Lilly, from a previous relationship. Born on June 22, 1952, he passed away on September 1, 2025. His indelible performances and his unwavering commitment to authentic storytelling have left an enduring mark on the cultural landscape, forever changing how Indigenous peoples are seen and heard on screen, solidifying his place as a true master of his craft and a cultural icon.